Path to the back door of Kincora House…. My next Novel read for learners of English.

Describe one simple thing you do that brings joy to your life.

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

READ ALONG WITH SEAMUS FROM ONE OF HIS ENGLISH LEARNING NOVELS, AND ENJOY THE RIDE.

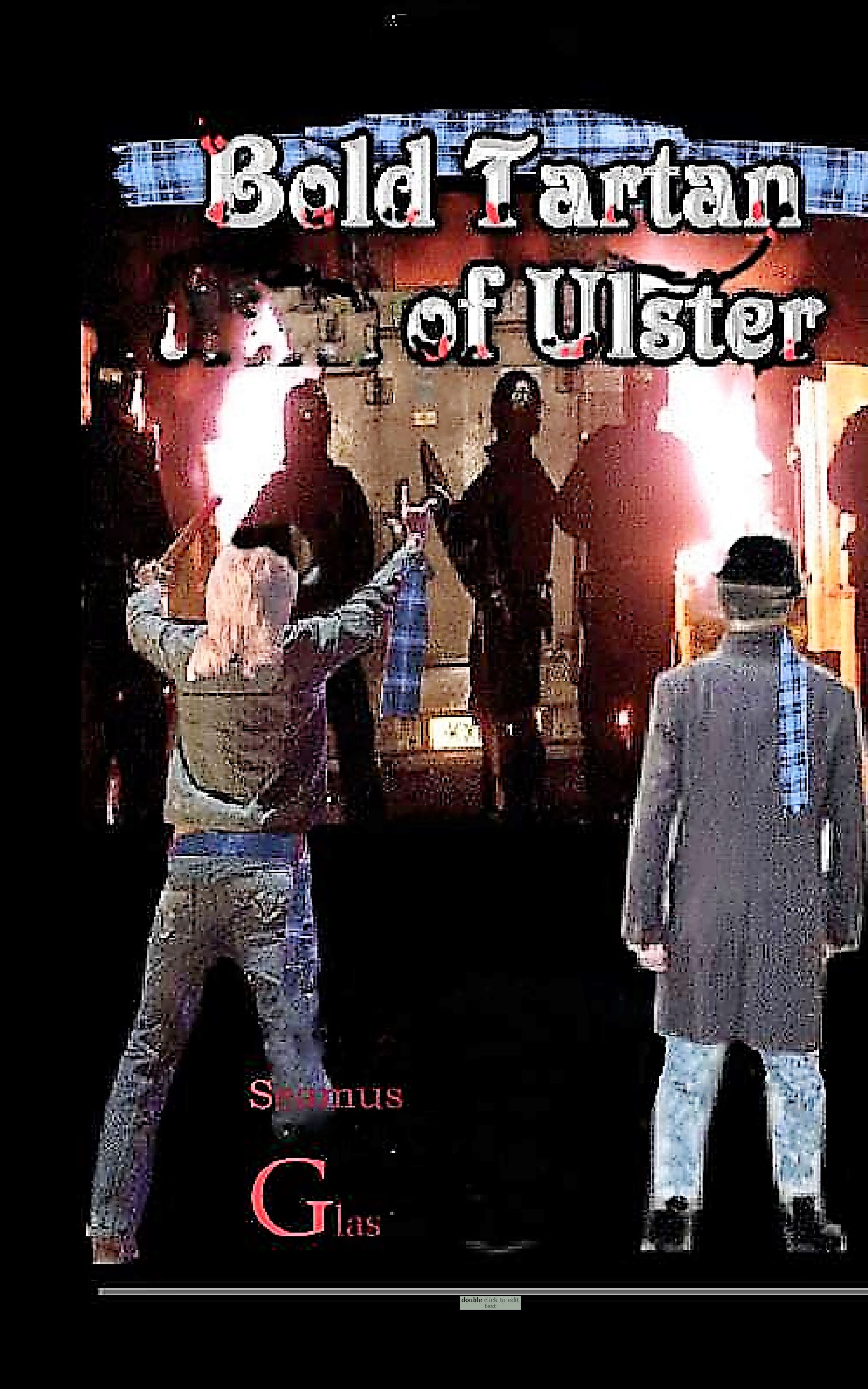

Bold Tartan of Ulster/Belfast

Seamus Glas, a pen-name for James Gray, a Scot Irish, and a citizen of Northern Ireland, United Kingdom was born to an English mother and a Scot Irish father 1956 in Belfast City Hospital in the province of Ulster. As a Presbyterian protestant, he remembers the commencement of the Ulster troubles with first-hand experience. He grew up east of the capital, Belfast, at a village called Dundonald, Co. Down, in which he claims, is the most panoramic county of Ulster. He fondly remembers the bold characters shaping his reality and forming his outlook today. He is one of five boys, and claims this is largely due to his parents whom he says, kept this part a secret. Today when back in the province, he writes when he can about his experiences…

View original post 236 more words

Pay with PayPal

Bold Tartan of Ulster/Novel/ E-Book/Paperback also on Amazon/Learn English easier with translatory inserts

A period in the 1970s Ulster Troubles. Our three juvenile protagonists become the antagonists hoping to dodge the rubber bullets and tear gas. Set in Belfast’s suburbs, it is set against a background of division between the Protestant Vigilantes and the Republican designs of a United Ireland. Will our trio survive the scrutiny of the Paramilitary leaders. This is another epilogue on the struggles of the remaining Scots Irish who are holding the Union between Ulster and England together whatever the cost.

£4.99

The Bolder Tartan rules, ok… Also available with Amazon

A sequel to the above novel….Our trio have moved up and into the Red Hand Commandos. A newly formed paramilitary orange group. To get to the source, you have to take risks. Meanwhile, Derna, the mother of one and a Green operative, is about to retire as a wealthy socialite. After a career as an undercover Op for the Provisional Irish Republican Army, she has made it her quest to seek out the baby she give away. To a protestant couple in the east of the city where her presence could be her undoing, she is prepared to take that risk. Will she get more than she bargained for as the brits have moved into the barracks nearby. Her long forgotten mother, a sleeper op from the old officials, has a safe house right down the road from them. Will Derna retire to enjoy her lavish lifestyle on the French Rivera. Or has someone she is yet to find out, have other motives for tracking her down.

$9.99

READ ALONG WITH SEAMUS FROM ONE OF HIS ENGLISH LEARNING NOVELS, AND ENJOY THE RIDE.

Bold Tartan of Ulster/Belfast

Seamus Glas, a pen-name for James Gray, a Scot Irish, and a citizen of Northern Ireland, United Kingdom was born to an English mother and a Scot Irish father 1956 in Belfast City Hospital in the province of Ulster. As a Presbyterian protestant, he remembers the commencement of the Ulster troubles with first-hand experience. He grew up east of the capital, Belfast, at a village called Dundonald, Co. Down, in which he claims, is the most panoramic county of Ulster. He fondly remembers the bold characters shaping his reality and forming his outlook today. He is one of five boys, and claims this is largely due to his parents whom he says, kept this part a secret. Today when back in the province, he writes when he can about his experiences and particularly his focus on the loyalist protestant cause when it commenced with honourable motives in light of imminent civil war. He attended the Boy’s High School Dundonald. In 1993, as a mature student, he embarked on a three-year language course at the Luton/London/Bedfordshire University, England, majoring in German. He is fluent in four European languages. Today he plans to embark on a part-time English language program teaching Native Americans on the reservation. He does not kill his food normally, though he enjoys fishing and accompanies the odd Elk hunt with his friends. No children that he knows of, though there still maybe the possibility of learning his parents secret.

April 1957-Falls Road Belfast county Antrim

Derna Travillion lay on the bed of a street house prepared for a secret rendezvous with her lack of moral love life. ‘Ah , you can judge me all ye want, ya wee bitch ye, but know ye this, have you ever asked yourself, have I ever walked in her sandals’…The midwife peeked left and right out of the window into the shimmer of a darkening street and its row of two up and down houses. Below, in a shadowy doorway, is her bodyguard. After bringing the velvet curtains together with a single swoop, she crosses herself and asks for forgiveness. After parting her legs and a push or two, Derna trains her ear on her midwife’s encouragement, ‘Who or where the fuck do I know you from’, she thought. ‘Butch bitch. Oh Jeesus, damn that wee Shite, he hates me already like no other.’

TEFL Qualified , you can now engaged my services online and your first lesson is free.

Grammar from your tongue sets the first impression for most educated folk. Your accent, mostly from uneducated folk is a determiner for them. Either way, setting you up for discriminating prejudgement or accepting you as an equal with a margin of time to work on it, is possible. It’s that instant in Northern Ireland. Prejudice is inherent in their culture and therefore mentality. Its source is suspicion and mistrust of outsiders. That’s just how it is in some parts of the UK. How to spot the pre-judger or the psycho-analyser is also on my menu. Either way, both are hostile and can be from an individual company or even a whole town/village as many have found in parts of the UK. So learning the native language in my belief should equip you with a matching skill of those who seem to have the upper hand as you pursue your new life. We all have our difficulties. Prejudgers and analysers are universally folks with hang-ups even against those of their own communities and indigenous. So don’t take it personally. But do learn to spot them and avoid spinning your wheels with them, which will have a long term improvement on your mental health. A hostile orientation in our growing multi cultural environment is not tolerated universally, though significant and it’s my intention to begin with some of Northern Ireland’s employers.

Unfortunately, some parts of the UK has not reached total protection against some discrimination like Ageism-Ethnicity and yes, even gender: conversely as the USA-Canada and other merging democracies advance on this theme, age continues to be top of the hang-up list. More noticeably a preference in some parts from empowering women even at the expense of their male colleagues and company profits. This can lead to lower revenue because of some promoting underqualified females for recruitment management where reports show empowerment as politically or culturally correct. though counterproductive. Because this often hidden growing cultural agenda is either coercive and therefore imposed, it is rarely talked over at the interview with some idea they are trying to outsmart the candidate. This is usually a big mistake, and most savvy candidates can sense what not to discuss. Besides, a savvy candidate will take in the company landscape whilst there. Good companies should bring to the attention immediately to all candidates, allowing the right to proceed or respectively decline. But this is not the US or Canada or even far eastern countries where all sorts of agencies have a better bearing on it. As a result, qualified males are often overlooked because of it. Northern Ireland, a model for this, isn’t exactly pulling the international brigade to their shores given this risky development. Protection based on the ethic ‘better candidate for the position’ must have done a reversal. Naturally gender plays a part and this can easily be monitoured and controlled, as is by a federal government in the US for example. They send an agent to cross-reference a corporate organisation’s hiring history of gender-age=ethnicity. This model does not come close to imposing protective legislation in the UK and often continues unabated. Reports show that this is particularly acute in NI.

English has its own tongues

SPEAKING AMERICAN

A History of English in the United States

By Richard W. Bailey

207 pp. Oxford University Press. $27.95.

In “Speaking American,” a history of American English, Richard W. Bailey argues that geography is largely behind our fluid evaluations of what constitutes “proper” English. Early Americans were often moving westward, and the East Coast, unlike European cities, birthed no dominant urban standard. The story of American English is one of eternal rises and falls in reputation, and Bailey, the author of several books on English, traces our assorted ways of speaking across the country, concentrating on a different area for each 50-year period, starting in Chesapeake Bay and ending in Los Angeles.

We are struck by the oddness of speech in earlier America. A Bostonian visiting Philadelphia in 1818 noted that his burgherly hostess casually pronounced “dictionary” as “disconary” and “again” as “agin.” William Cullen Bryant of Massachusetts, visiting New York City around 1820, wrote not about the “New Yawkese” we would expect, but about locutions, now vanished, like “sich” for “such” and “guv” for “gave.” Even some aspects of older writing might throw us. Perusing The Chicago Tribune of the 1930s, we would surely marvel at spellings like “crum,” “heven” and “iland,” which the paper included in its house style in the ultimately futile hope of streamlining English’s spelling system.

A challenge for a book like Bailey’s, however, is the sparseness of evidence on earlier forms of American English. The human voice was unrecorded before the late 19th century, and until the late 20th recordings of casual speech, especially of ordinary people, were rare. Meanwhile, written evidence of local, as opposed to standard, language has tended to be cursory and of shaky accuracy.

For example, the story of New York speech, despite the rich documentation of the city over all, is frustratingly dim. On the one hand, an 1853 observer identified New York’s English as “purer” than that found in most other places. Yet at the same time chronicles of street life were describing a jolly vernacular that has given us words like “bus,” “tramp” and “whiff.” Perhaps that 1853 observer was referring only to the speech of the better-off. But then just 16 years later, a novel describes a lad of prosperous upbringing as having a “strong New York accent,” while a book of 1856 warning against “grammatical embarrassment” identifies “voiolent” and “afeard” as pronunciations even upwardly mobile New Yorkers were given to. So what was that about “pure”?

Possibly as a way of compensating for the vagaries and skimpiness of the available evidence, Bailey devotes much of his story to the languages English has shared America with. It is indeed surprising how tolerant early Americans were of linguistic diversity. In 1903 one University of Chicago scholar wrote proudly that his city was host to 125,000 speakers of Polish, 100,000 of Swedish, 90,000 of Czech, 50,000 of Norwegian, 35,000 of Dutch, and 20,000 of Danish.

What earlier Americans considered more dangerous to the social fabric than diversity were perceived abuses within English itself. Prosecutable hate speech in 17th-century Massachusetts included calling people “dogs,” “rogues” and even “queens” (though the last referred to prostitution); magistrates took serious umbrage at being labeled “poopes” (“dolts”). Only later did xenophobic attitudes toward other languages come to prevail, sometimes with startling result. In the early years of the 20th century, California laws against fellatio and cunnilingus were vacated on the grounds that since the words were absent from dictionaries, they were not English and thus violations of the requirement that statutes be written in English.

Ultimately, however, issues like this take up too much space in a book supposedly about the development of English itself. Much of the chapter on Philadelphia is about the city’s use of German in the 18th century. It’s interesting to learn that Benjamin Franklin was as irritated about the prevalence of German as many today are about that of Spanish, but the chapter is concerned less with language than straight history — and the history of a language that, after all, isn’t English. In the Chicago chapter, Bailey mentions the dialect literature of Finley Peter Dunne and George Ade but gives us barely a look at what was in it, despite the fact that these were invaluable glimpses of otherwise rarely recorded speech.

Especially unsatisfying is how little we learn about the development of Southern English and its synergistic relationship with black English. Bailey gives a hint of the lay of the land in an impolite but indicative remark about Southern child rearing, made by a British traveler in 1746: “They suffer them too much to prowl amongst the young Negroes, which insensibly causes them to imbibe their Manners and broken Speech.” In fact, Southern English and the old plantation economy overlap almost perfectly: white and black Southerners taught one another how to talk. There is now a literature on the subject, barely described in the book.

On black English, Bailey is also too uncritical of a 1962 survey that documented black Chicagoans as talking like their white neighbors except for scattered vowel differences (as in “pin” for “pen”). People speak differently for interviewers than they do among themselves, and modern linguists have techniques for eliciting people’s casual language that did not exist in 1962. Surely the rich and distinct — and by no means “broken” — English of today’s black people in Chicago did not arise only in the 1970s.

Elsewhere, Bailey ventures peculiar conclusions that may be traceable to his having died last year, before he had the chance to polish his text. (The book’s editors say they have elected to leave untouched some cases of “potential ambiguity.”) If, as Bailey notes, only a handful of New Orleans’s expressions reach beyond Arkansas, then exactly how was it that New Orleans was nationally influential as the place “where the great cleansing of American English took place”?

And was 17th-century America really “unlike almost any other community in the world” because it was “a cluster of various ways of speaking”? This judgment would seem to neglect the dozens of colonized regions worldwide at the time, when legions of new languages and dialects had already developed and were continuing to evolve. Of the many ways America has been unique, the sheer existence of roiling linguistic diversity has not been one of them.

The history of American English has been presented in more detailed and precise fashion elsewhere — by J. L. Dillard, and even, for the 19th century, by Bailey himself, in his underread “Nineteenth-Century English.” Still, his handy tour is useful in imprinting a lesson sadly obscure to too many: as Bailey puts it, “Those who seek stability in English seldom find it; those who wish for uniformity become laughingstocks.”

YOUR ENGLISH GENRE,

KNOW YOUR TENSES AND GRAMMAR