Schwartzer Scheffehund

Describe one simple thing you do that brings joy to your life.

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

READ ALONG WITH SEAMUS FROM ONE OF HIS ENGLISH LEARNING NOVELS, AND ENJOY THE RIDE.

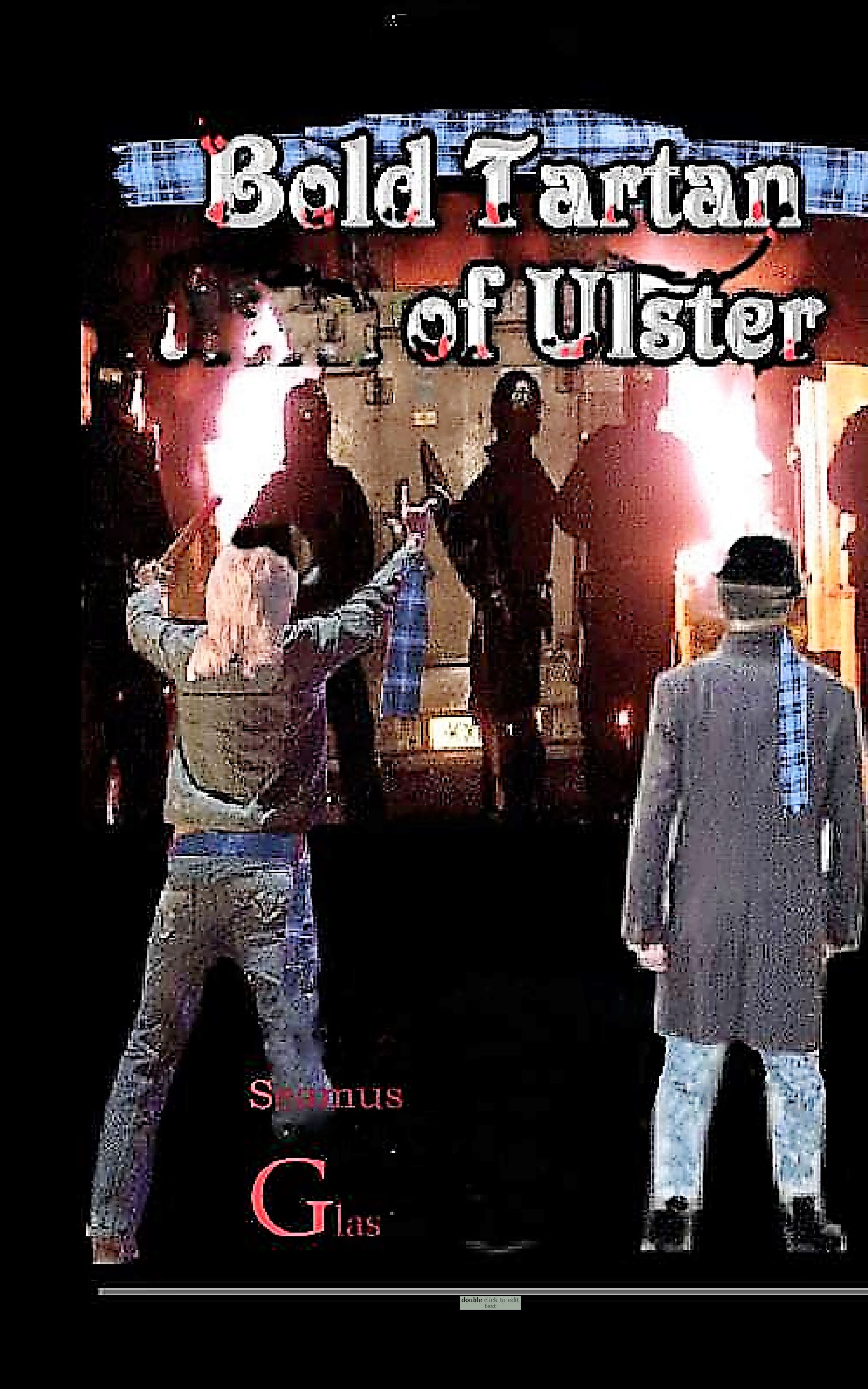

Bold Tartan of Ulster/Belfast

Seamus Glas, a pen-name for James Gray, a Scot Irish, and a citizen of Northern Ireland, United Kingdom was born to an English mother and a Scot Irish father 1956 in Belfast City Hospital in the province of Ulster. As a Presbyterian protestant, he remembers the commencement of the Ulster troubles with first-hand experience. He grew up east of the capital, Belfast, at a village called Dundonald, Co. Down, in which he claims, is the most panoramic county of Ulster. He fondly remembers the bold characters shaping his reality and forming his outlook today. He is one of five boys, and claims this is largely due to his parents whom he says, kept this part a secret. Today when back in the province, he writes when he can about his experiences…

View original post 236 more words

Pay with PayPal

Bold Tartan of Ulster/Novel/ E-Book/Paperback also on Amazon/Learn English easier with translatory inserts

A period in the 1970s Ulster Troubles. Our three juvenile protagonists become the antagonists hoping to dodge the rubber bullets and tear gas. Set in Belfast’s suburbs, it is set against a background of division between the Protestant Vigilantes and the Republican designs of a United Ireland. Will our trio survive the scrutiny of the Paramilitary leaders. This is another epilogue on the struggles of the remaining Scots Irish who are holding the Union between Ulster and England together whatever the cost.

£4.99

The Bolder Tartan rules, ok… Also available with Amazon

A sequel to the above novel….Our trio have moved up and into the Red Hand Commandos. A newly formed paramilitary orange group. To get to the source, you have to take risks. Meanwhile, Derna, the mother of one and a Green operative, is about to retire as a wealthy socialite. After a career as an undercover Op for the Provisional Irish Republican Army, she has made it her quest to seek out the baby she give away. To a protestant couple in the east of the city where her presence could be her undoing, she is prepared to take that risk. Will she get more than she bargained for as the brits have moved into the barracks nearby. Her long forgotten mother, a sleeper op from the old officials, has a safe house right down the road from them. Will Derna retire to enjoy her lavish lifestyle on the French Rivera. Or has someone she is yet to find out, have other motives for tracking her down.

$9.99

READ ALONG WITH SEAMUS FROM ONE OF HIS ENGLISH LEARNING NOVELS, AND ENJOY THE RIDE.

Bold Tartan of Ulster/Belfast

Seamus Glas, a pen-name for James Gray, a Scot Irish, and a citizen of Northern Ireland, United Kingdom was born to an English mother and a Scot Irish father 1956 in Belfast City Hospital in the province of Ulster. As a Presbyterian protestant, he remembers the commencement of the Ulster troubles with first-hand experience. He grew up east of the capital, Belfast, at a village called Dundonald, Co. Down, in which he claims, is the most panoramic county of Ulster. He fondly remembers the bold characters shaping his reality and forming his outlook today. He is one of five boys, and claims this is largely due to his parents whom he says, kept this part a secret. Today when back in the province, he writes when he can about his experiences and particularly his focus on the loyalist protestant cause when it commenced with honourable motives in light of imminent civil war. He attended the Boy’s High School Dundonald. In 1993, as a mature student, he embarked on a three-year language course at the Luton/London/Bedfordshire University, England, majoring in German. He is fluent in four European languages. Today he plans to embark on a part-time English language program teaching Native Americans on the reservation. He does not kill his food normally, though he enjoys fishing and accompanies the odd Elk hunt with his friends. No children that he knows of, though there still maybe the possibility of learning his parents secret.

April 1957-Falls Road Belfast county Antrim

Derna Travillion lay on the bed of a street house prepared for a secret rendezvous with her lack of moral love life. ‘Ah , you can judge me all ye want, ya wee bitch ye, but know ye this, have you ever asked yourself, have I ever walked in her sandals’…The midwife peeked left and right out of the window into the shimmer of a darkening street and its row of two up and down houses. Below, in a shadowy doorway, is her bodyguard. After bringing the velvet curtains together with a single swoop, she crosses herself and asks for forgiveness. After parting her legs and a push or two, Derna trains her ear on her midwife’s encouragement, ‘Who or where the fuck do I know you from’, she thought. ‘Butch bitch. Oh Jeesus, damn that wee Shite, he hates me already like no other.’

TEFL Qualified , you can now engaged my services online and your first lesson is free.